Prindsen

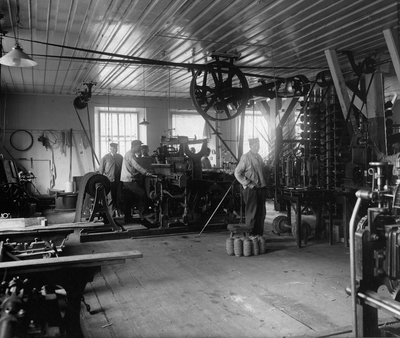

For almost three years, I have been working at the historic weaving mill at Prinds Christian Augusts Minde, Prindsen, in central Oslo. It is a large workshop with six older industrial looms, a sectional warp beam and two winding machines. The building and the inventory in the weaving workshop have been protected as part of a preservation plan for Prindsen since 2009 1.

Prindsen was established in 1809 as an institution for convicts, the homeless and people with mental disorders. It opened in 1819 after a long planning period 2. It was a closed facility and the inmates were prisoners, often held there without court orders. To improve the social situation of the institution and to exploit available labour, a factory was built with production workshops, completed in 1833 3. At Prindsen, everyone was put to work, regardless of their condition. Towards the street there was a shop that sold products made at the institution. In addition to the weaving workshop there were carpentry, shoemaking and rope-making workshops, a steam kitchen, laundry facilities and a quarry. Every workshop had managers employed with responsibility for production. Being imprisoned at Prindsen was not considered part of a process of improving people's state or position, nor did their work experience facilitate employment outside the institution.

The 2009 protection order from the Directorate for Cultural Heritage describes the activity of Prindsen in the 1900s as follows: By the late 1800s, Christiania Kommunale Sindssygeasyl [Christiania Municipality Asylum] was the country's second largest after Gaustad. The men's department of the asylum moved in 1905 and the women's department in 1908 to Dikemark [a new institution quite far outside of the city]. Kristiania Tvangsarbeidsanstalt [a penal labour institution] was closed in 1915, and 174 male convicts were transferred to the new institution Opstad at Jæren. However, the institution in Storgata continued with related activities. In Mangelsgården [part of the property], Fattigvesenet [a municipal agency supporting the poor] established a home for elderly people, and later various social functions run by the municipality 4.

Prindsen is today managed by a municipal department called Omsorgsbygg. There are still people living on the property in social housing, although Prindsen is changing rapidly, with designers, artists and musicians establishing themselves in the various buildings on the site. The daily operations in the weaving workshop were closed in the 1970s, but were sporadically in use until the late 1990s.

Prindsen is the only place in the Oslo area where it is possible to see a larger selection of machines used in the textile industry, the backbone of industrial activity in Christiania in the latter half of the 19th century. I am working on restoring one of the looms for demonstration. Two of the looms are of the same construction as the ones at Sjølingstad Woollen Mill, but newer. They are from 1951, and manufactured by Texo in Norrköping, Sweden. The local Directorate for Cultural Heritage, Byantikvaren, allows the looms to be used. Still, at Prindsen, the loom will mainly be for educational purposes. Larger quantities, or more complex qualities I will produce elsewhere.

The workshop at Prindsen is a place for developing conversations, with students, colleagues and the general public. I am collaborating with the Oslo Museum, Arbeidermuseet, the Oslo City Archives and the Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology on activating the space.

My presence in the weaving workshop at Prindsen allows for an exploration of the social history of the institution, aspects of penal labour, the treatment of people on the margins of society, social distress, mental disorders and degradation. I read the novel The Thief's Journal by Jean Genet in my late teens. It is an autobiographical description of Genet's experiences as he wanders through the roughest areas of central European cities in the 1930s, participating in various subcultures along the way. He is gay, a beggar, a prostitute, a thief and in motion. Genet often describes the fabrics and clothes worn by the characters in great detail. The first sentences of the book are: Convicts' garb is striped pink and white. Though it was at my heart's bidding that I chose the universe wherein I delight, I at least have the power of finding therein the many meanings I wish to find: there is a close relationship between flowers and convicts 5.

I have seen Prindsen as both a commitment and a necessity. Based on the development of my work, and the clarification of the fundamental aspects of my practice, I am continuously expanding my thinking on how to relate to Prindsen - as a place where my work can continue, from where I can think, act and participate.

-

Lars Erik Eibak Bru and Linda Veiby, Vernevedtak Prinds Christian Augusts Minde, Riksantikvaren, Oslo, 2009. ↩

-

Sigurd Grieg, Norsk Tekstil, vol. 1, Norske Tekstilfabrikers Hovedforening, Oslo, 1948, p. 191. ↩

-

Wenche Blomberg, Prinds Christian Augusts Minde - historie og visjoner om de fattiges kvartal, Prindsens venner, Oslo, 2006, p. 9. ↩

-

Vernevedtak Prinds Christian Augusts Minde, p. 10. ↩

-

Jean Genet, The Thief's Journal, Grove Press, New York, 1964, p. 7. ↩